Creation

Every

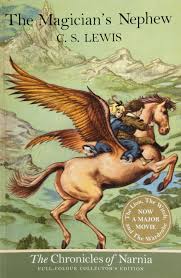

storyteller “creates” (Tolkien would say, sub-creates) a world. In fact, both C.

S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien wrote creation stories: Lewis’s The Magician’s Nephew portrays Aslan singing

Narnia into existence; and in The

Silmarillion, Tolkien beautifully describes the formation of Middle-earth. Even

story-tellers who don’t write explicit creation accounts fashion worlds for readers

to enjoy. Flannery O’Connor, author of short stories and novels, observed that

the novelist always has to create a world, and a believable one.

Every

storyteller “creates” (Tolkien would say, sub-creates) a world. In fact, both C.

S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien wrote creation stories: Lewis’s The Magician’s Nephew portrays Aslan singing

Narnia into existence; and in The

Silmarillion, Tolkien beautifully describes the formation of Middle-earth. Even

story-tellers who don’t write explicit creation accounts fashion worlds for readers

to enjoy. Flannery O’Connor, author of short stories and novels, observed that

the novelist always has to create a world, and a believable one.

Redemption

Screenwriter Brian Godawa observes that stories “are finally, centrally, crucially, primarily, mostly about redemption.” Redemption is a reversal or a resolution of that which has gone awry. It’s quite simple in some stories: Peter Rabbit learns to obey his mother; and the runaway bunny discovers that, no matter where she goes, her mother will always seek and find her. In many stories redemption is delightfully complex. In Field of Dreams, for example, Ray Kinsella’s angst is resolved only after building a baseball field and traveling hither and yon in response to that unrelenting voice. In Groundhog Day, Phil has to relive the second day of February three thousand six hundred and fifty times to learn how to love.

Screenwriter Brian Godawa observes that stories “are finally, centrally, crucially, primarily, mostly about redemption.” Redemption is a reversal or a resolution of that which has gone awry. It’s quite simple in some stories: Peter Rabbit learns to obey his mother; and the runaway bunny discovers that, no matter where she goes, her mother will always seek and find her. In many stories redemption is delightfully complex. In Field of Dreams, for example, Ray Kinsella’s angst is resolved only after building a baseball field and traveling hither and yon in response to that unrelenting voice. In Groundhog Day, Phil has to relive the second day of February three thousand six hundred and fifty times to learn how to love.

The Hero

In many stories a special person is chosen to rescue those afflicted with misfortune or injustice. So in The Hobbit, Bilbo Baggins accompanies a group of dwarfs to retrieve their treasure in theLonely Mountain

In many stories a special person is chosen to rescue those afflicted with misfortune or injustice. So in The Hobbit, Bilbo Baggins accompanies a group of dwarfs to retrieve their treasure in the

Death and Resurrection

Joseph Campbell noted that death and resurrection is a

natural part of hero stories. Mostly it’s virtual

death and rebirth late in the tale. That happens in The Hobbit when Bilbo is knocked unconscious during the Battle of

Five Armies. He had been wearing the ring that made him invisible, so he is

thought to be missing or dead. When he comes round and hears the voice of a man

searching for him, he takes off the ring and identifies himself.

No comments:

Post a Comment